Atlas Shrugged, Part I (2011) – Movie Review

By Robert L. Jones | April 18, 2011

Back to the Old Drawing Board

[xrr rating=3/5]

“A house can have integrity, just like a person; and just as seldom….No two buildings have the same purpose. The purpose, the site, the material determine the shape. Nothing can be reasonable or beautiful unless it’s made by one central idea, and the idea sets every detail. A building is alive, like a man. Its integrity is to follow its own truth, its one single theme, and to serve its own single purpose.” – Ayn Rand, The Fountainhead, 1943.

The same goes for movies. John Aglialoro, the multimillionaire who just spent nearly $20 million of his own money to finance the movie version of Atlas Shrugged, would have done well to re-read Rand’s ultimate aesthetic statement before embarking on the Quixotic task of adapting her ultimate philosophical statement to the big screen.

Therein lies the problem. Ever since Rand herself wrote the screenplay for Warner Bros.’ 1949 version of The Fountainhead, she – as well as her Objectivist progeny – have been on guard in protecting the thematic integrity of any filmed version of her next and final novel, Atlas Shrugged. Rand got burned by studio chief Jack Warner and producer Henry Blanke on protecting The Fountainhead from being savaged by puritanical busybodies – not the least of which was The Catholic Legion – from slashing out objectionable “selfish” and allegedly misanthropic quotes from the final shooting script.

Well, I am happy to report that Atlas Shrugged, Part I is intellectually and philosophically consistent to the novel. Well done, boys!

But, I don’t go to the movie theater to watch philosophically consistent messages. I go to be swept away by a great plot, intelligent and adept screenwriting, intuitive performances, breathtaking cinematography, concise editing, and an impassioned soundtrack. The inclusion of John Aglialoro’s name as Brian Patrick O’Toole’s co-scenarist, and the predominance of Atlas Society’s David Kelley’s name in the credits, spoke volumes about the (understandably) misplaced priority of making certain that this film passed ideological muster – at the expense of the movie’s aesthetic integrity. I don’t fault Aglialoro and Kelley for standing guard over the movie’s philosophy, but would like to gently ask them, “When it comes to the movie’s artistic unity, who’s minding the store?”

I have but one question for O’Toole and director Paul Johansson: Do you understand which novel you were tasked with bringing to the silver screen? I honestly don’t think they did. I am not an Objectivist nitpicker with a laundry list of must-have scenes and lines. To me, Atlas Shrugged is not my Holy Bible. But, I would assume that any filmmaker worth his salt would regard the responsibility of making the movie version as akin to the Holy Grail. To treat its presentation and execution as a quest – not a slap-dash run to the finish line.

For months now, the movie’s cheerleaders have been hyping this production with the strangely-admitted caveat that even if the movie isn’t hot stuff, that at least it will improve sales of the book version. I am not being flippant, but Ayn Rand – who worked for Cecil B. DeMille and Howard Hughes’s RKO Pictures, and wrote for Hal Wallis at Paramount – would probably advise those selfsame cheerleaders, “Check your premises.” Movies were a religion for Rand, and while she had her limitations as a screenwriter, she fully understood that the unique art of the cinema was meant to be larger than life.

I liked Atlas Shrugged, Part I. I also like “The Flintstones,” vanilla ice cream, and playing a round of checkers. But, I love great works of art, such as Bernini’s David, Arturo Toscanini’s 1936 recording of Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony, and Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather (Parts I and II). Nobody ever went to a performance of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet expecting an interpretation of the star-crossed lovers’ like affair.

I like The Godfather, Part III. Strangely, this film – which first saw its chances of being made for the big screen when Godfather producer Albert S. Ruddy proposed putting Rand’s magnum opus on celluloid – has come full-circle. It reminds me eerily of Coppola’s ill-fated performance in The Godfather, Part III. That’s not Francis Ford Coppola, but his daughter, Sofia Coppola. And that’s Sofia Coppola the actress in way over her head, not the somewhat competent director.

Don’t blame the actors for Atlas Shrugged’s flaws: Most cast members do an excellent job. Taylor Schilling, as heroine Dagny Taggart, the tough executive out to save her grandfather’s railroad, is perfectly physically cast – her appearance recalls Eva Marie Saint during the 1950s. Her performance is competent, and at times, moving. (There are moments where she seems to be searching for a bit of dialogue – then finding it – but I blame Johansson for that stumbling).

Grant Bowler as steel magnate Hank Rearden does a superb job. He really groks the part, and grounds the movie with his incisive performance. He’s solid and masculine enough to carry the movie on his shoulders (no pun intended), and only relies on nuance sparingly and always apropos. Michael Lerner and Jon Polito bring decades of charater acting chops to the movie’s villain roles, duplicitous lobbyist Wesley Mouch and crony capitalist Orren Boyle, respectively. There were moments I was inwardly cheering on Graham Beckel’s fiery performance as oil baron Ellis Wyatt.

Where this movie suffers is primarily in its heavy-handed and lackluster script. It reads more like a serialization of a Reader’s Digest condensed book translated into some obscure tongue, and then back into English. I had seen an interview with screenwriter O’Toole a couple months ago and he did a marvelous job describing the process of adapting a novel to the screenplay format. He fully understands the importance of condensing and editing.

The problem is that O’Toole condensed the novel to such a point as to render the final product confining and claustrophobic. What seems to totally elude him is that a movie’s pace is not a checklist of shots and scenes to breeze through. Alfred Hitchcock understood that a movie’s suspense required not only a breakneck chase scene, but prolonged, fingernail-biting moments of waiting and inactivity. Like a symphony, a movie must have equal portions of tension and release.

Without this dynamic, a film becomes monotonous. I have often thought that Atlas Shrugged should have been filmed in the late 1950s or early 1960s by Otto Preminger, when he was at the peak of his power of making sprawling epics that immortalized their source material, whether Leon Uris’s Exodus or Allen Drury’s Advise and Consent. Preminger had the discipline and vision to do full justice to these modern literary classics.

The answer to the generic feel of Atlas Shrugged, Part I lies not in the question “Who Is John Galt?” but rather in asking, “Who Is Paul Johansson?” Based upon this movie, the answer is: An artistic non-entity, rather much like Rand’s architectural second-rater Peter Keating. Most critics have lambasted the “made for television” aesthetic quality of this movie. That is an insult to many of my favorite television programs and miniseries, such as “The Twilight Zone,” “The A-Team,” and “Shogun.”

Why is it, that in the 21st century we can have stupendous miniseries with big-screen production values, like Band of Brothers and John Adams, but this movie feels more like a straight-to-video feature? The question answers itself.

From the overuse of subtitles to denote the movie’s locations – we are told that Hank and Dagny would find Ivy Starnes in Durrance, Louisiana, so why was it necessary for a title that says “DURRANCE, LOUISIANA”? – to the breezy pace of the movie’s plot revelations, Atlas Shrugged’s makers seemed to believe that imparting the gravitas of the book was beside the point.

Atlas Shrugged has a great mystery story. The finding of Galt’s motor was a mystery but in the movie, Rearden seems to find it on an old Filofax or Lexus/Nexus search. The identity of John Galt was a mystery. People ask, as a throwaway line, “Who Is John Galt?” in the book, admitting their weary helplessness in the face of everyday malaise; in the movie, a shadowy, hulking guy in a fedora, stalks industrialists, and key characters place more weight on the question than the anchor holding the U.S.S. Nimitz to the sea floor.

The character of Eddie Willers, who is the key to finding out Galt’s identity, is rendered superfluous in the movie – the movie’s ending narration at the end of part one reveals a spoiler not meant to be divulged until way later as to Galt’s identity and mission. Edi Gathegi’s role is basically reduced to being Dagny’s receptionist, relaying phone calls and introducing visitors to her office. Note to the movie’s producers: If you’re going to make Eddie Willers black, don’t be so obvious by making him into a male version of Nichelle Nichols’ character Lt. Uhura in “Star Trek.”

Atlas Shrugged, Part I, comes in at 102 minutes. The standard for a Hollywood drama has long been 120 minutes – eighteen minutes difference.

With eighteen additional minutes, they could have made a picture that breathed. It wouldn’t have felt as though the whole movie consisted of hopping from formal party to velvet-rope restaurant to smoke-filled bar. When, for example, Francisco d’Anconia (Jsu Garcia) approached Hank Rearden to inquire where the partygoers attending Rearden’s anniversary celebration would be without Rearden’s munificence and charity,it would have underscored Francisco’s inquiry if a window – out of which a bleak and forboding tundra could be seen for a few seconds – had been available. Or, if Ellis Wyatt’s revelry with Hank and Dagny celebrating the successful run on the John Galt Line were punctuated with him throwing his champagne glass against the wall (indicating his fatalistic sense of the future), it would have made for so much more poignancy than his mostly perfunctory exit.

And, one other thing: Don’t insult the intelligence of railroad buffs such as I by trying to pass off a Chicago-area Metra commuter train as a cross-country mainline passenger train. Don’t show me shot after shot of freight yards without one single hopper, boxcar, or switch engine emblazoned with the Taggart emblem. Don’t have the engineer driving the diesel version of the Amtrak Acela on the maiden voyage of the John Galt Line look and dress more like the cashier of an Amtrak regional line snack bar.

These, and so many other, lost opportunities make for the demarcation line between an acceptable movie and a classic. With more soul-searching and forethought, this movie could have been a classic.

You’ve got two more rounds, gentlemen. Fire Johansson and O’Toole, and get some people who know movies to pen and shoot the next two installments. For God’s sake, act as if you care you’re filming an epic.

Topics: Dramas, Epic Movies, Movie Reviews, Political Dramas, Sci-Fi Movies |

Candy (1968) – Movie Review

By Bruce Eckerd | October 6, 2009

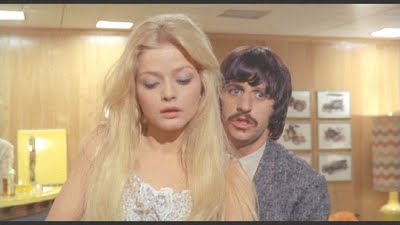

Ewa Aulin and Richard Starkey in a scene from "Candy"

Everyone Wants a Taste….

[xrr rating=2.5/5]

Candy. Featuring Charles Aznavour, Marlon Brando, Richard Burton, James Coburn, John Huston, Walter Matthau, Ringo Starr, Ewa Aulin, John Astin, Elsa Martinelli, Sugar Ray Robinson, Anita Pallenberg, Lea Padovani, Florinda Bolkan, Marilù Tolo, Nicoletta and Machiavelli. Original Music by Dave Grusin. Screenplay by Buck Henry. Based upon the novel by Mason Hoffenberg and Terry Southern. Cinematography by Giuseppe Rotunno. Film Editing by Giancarlo Cappelli and Frank Santillo. Directed by Christian Marquand. (Cinerama Realsing Corporation, 1968, Color, 124 minutes. MPAA Rating: R).

The 1960s, particularly the latter half of the decade, were a time of sexual discovery, personal awakening, and loosening censorship. Movies like Midnight Cowboy and Myra Breckinridge–whose sexual themes would have had them banned only a few short years before–were suddenly making it onto the big screen. Candy is one of the earliest examples of this trend.

Candy is possibly the quintessential over-the-top 60s movie. If you’re looking for faults, it has its share. But frankly, if you like the 60s I don’t see you not liking at least something about this movie. For starters, it practically has an all-star cast, Marlon Brando, John Huston, Walter Matthau, Richard Burton, and James Coburn. Speaking of “stars,” Ringo Starr makes an appearance as the Mexican gardener, Manuel, which is probably one of the few reasons people still remember this movie.

Like most films from the late 60s and early 70s, Candy was meant to satirize “the Establishment.” (There’s just something about a preemptive war that gets certain youngsters feisty.) And what better model to emulate than the ultimate satirical scourge, Voltaire’s Candide. Think of Candy as Candide’s female counterpart and instead of 18th Century France, her travels are through the American landscape of the late 60s when flower power was at its height, and psychedelic drugs were handed out like (no pun intended) candy on Halloween.

The absurd opening sequence of a celestial starscape is certainly made more than endurable by the psychedelic rock soundtrack produced by the Byrds (“Turn, Turn, Turn”). At the beginning of an average day, we see Candy Christian (Ewa Aulin) daydreaming in a classroom where her father, T.M. Christian (John Astin), is also her teacher. He angrily stirs her from her temporary mind trip and when she calls him daddy, she only gets in more trouble and is asked to stay after class. Her father undoubtedly represents the fuddy duddy conservative, the object of scorn to this day by unwashed hippies everywhere. She has to cut their after class conference short however, as British poet laureate MacPhisto (Richard Burton) is making an appearance at the school this day.

Throughout the remainder of the film, Candy’s exploits are followed closely as she is pursued by men of all walks of life, including an army general, a surgeon, a film director, a swami, her uncle, and even her own father, who at the time has lost most of his mental faculties due to an unfortunate run in with some enraged Mexican women. The plot is somewhat weak and to a large extent involves only Candy’s search for her father who goes missing after having surgery on his head somewhere in the middle of the film.

One of the weaker parts of the film is the very passive role Candy plays in moving the plot along. She’s more of an observer of the bizarre events that occur to her. Instead of being an active catalyst in them is instead unwillingly drawn into them. In a sense, this is a reflection of the overwhelming existentialist philosophy of the time it was made, where people, particularly younger people, saw the world as absurd and unstable, due largely to the crumbling social structure and the Vietnam War.

Although it clocks in at a lengthy 124 minutes, a bit long for a screwball comedy, the film manages to keep your attention, especially with the help of new and interesting characters and locations which are introduced regularly. In fact, the only part of the film that really drags is a scene towards the end where a swami, played by Marlon Brando, babbles endlessly in faux-spiritual platitudes that were so popular at the time (did Francis Ford Coppola use this as a basis for Brando’s rambling psychoses in Apocalypse Now?). This scene runs for about 15 minutes which is way too long, especially for a scene that has little to do with the plot (threadbare as it is).

Candy has not aged well, and a basic understanding and appreciation of the culture of the late 60s is definitely needed in order to get any enjoyment out of the film. To a fan of this culture, the humor captures the spirit of the age well, and ranges from the predictable to the absurd, but always to the extreme. For a fan of the 60s who has not yet seen this film, it represents a fairly accurate window into the over-the-top pop culture that dominated the time.

Topics: Comedies, Coming of Age Movies, Movie Reviews |

Mirage (1965) – Movie Review

By Robert L. Jones | November 4, 2008

George Kennedy, Diane Baker, and Gregory Peck in “Mirage”

George Kennedy, Diane Baker, and Gregory Peck in “Mirage”

Man On the Run with Nowhere to Go

[xrr rating=4.5/5]

Mirage. Starring Gregory Peck, Diane Baker, Walter Matthau, Kevin McCarthy, Jack Weston, Leif Erickson, Walter Abel, George Kennedy, and Robert H. Harris. Music by Quincy Jones. Cinematography by Joseph MacDonald. Art direction by Frank Arrigo and Alexander Golitzen. Costume design by Jean Louis. Makeup by Bud Westmore. Edited by Ted J. Kent, A.C.E.. Screenplay by Peter Stone. Based on a story by Walter Ericson (nom de plume for Howard Fast). Directed by Edward Dmytryk. (Universal Pictures, 1965, Black and white, 108 minutes. MPAA Rating: Approved.)

Gregory Peck stars as David Stillwell, a man with a secret. The problem is: He doesn’t know he has a secret, because he is suffering from amnesia. Thus begins this psychological thriller in the Hitchcock tradition, set in New York City in the mid 1960s.

Peck, feeling that he’s lost his grip on reality, and needing to actualize his existence, starts down the path of reconstructing his life. Because he has amnesia, he can’t remember having any friends. He visits a psychiatrist (played with passion and intelligence by Robert H. Harris) and hires an easy-going private eye (Walter Matthau) to investigate who he really is, and find out his identity. Early on, he runs into old flame, Sheila, played by the beautiful and underrated Diane Baker (fresh off of Hitchcock’s dark Marnie). She turns out to be even more of a cipher than Peck, refusing clues to his queries about his identity. “I want to remember who I am!” Peck rages at Baker. Her tortured reply singularly sums up his bizarre and paradoxical world: “Not remembering is the only thing keeping you alive!”

So, as you can see, this is a neat twist on the amnesia flick, and I’m going to stop here, because I don’t want to give any more of the plot of away. The intelligent script by Peter Stone (Charade, The Taking of Pelham 1-2-3) moves alternately fast-and-furious/slow-and-langorous. Mirage is chock full of great performances: George Kennedy and Jack Weston give two of the best portrayals of sociopathic, ruthless hired killers ever; Leif Erickson stars as “The Major,” an equally ruthless industrialist bent on prying the secret loose from Peck’s clouded mind; Kevin McCarthy is glib and smarmy as the sycophantic Josephson, and veteran actor Walter Abel is suave and conflicted as Peck’s mentor, Charles Calvin.

Director Edward Dmytryk–best known for his masterwork The Caine Mutiny, and blacklisted during the McCarthy years–directed Mirage really tight: There are no dissolves–every cut is literally a cut, and the breakneck pace of the chase scenes further establishes Peck as a man alone, being kept on a long leash. Dmytryk broke with tradition by editing even the flashback scenes with straight cuts. There is also no cloudy, “dreamy,” like soft-focus, either–Gregory Peck’s recollections are in fact magnified with greater clarity than action in the present tense–and it works beautifully.

Notching the tension up even further is Quincy Jones’ jazzy and urbane soundtrack, which draws on the “crime jazz” genre created by Elmer Bernstein and Henry Mancini and looks forward to Jones’ own soundtrack for In the Heat of the Night.

This is a totally solid and taut thriller, which has just been released by Universal as part of its Gregory Peck collection. Included in this special box set are also To Kill a Mockingbird, Cape Fear, Arabesque, The World in His Arms, and Captain Newman, M.D.

Robert L. Jones is a photojournalist living and working in Minnesota. His work has appeared in Black & White Magazine, Entrepreneur, Hoy! New York, the New York Post, RCA Victor (Japan), Scene in San Antonio, Spirit Magazine (Canada), Top Producer, and the Trenton Times. Mr. Jones is a past entertainment editor of The New Individualist.

Topics: Classic Movies, Dramas, Movie Reviews, Suspense Movies |

Expelled: No Intelligence Allowed (2008) – Movie Review

By Robert L. Jones | August 5, 2008

Who Made Who? (with apologies to Angus Young)

[xrr rating=3/5]

Expelled: No Intelligence Allowed. Featuring Ben Stein, Peter Atkins, Hector Avalos, Doug Axe, David Berlinski, Walter Bradley, Bruce Chapman, Caroline Crocker, Richard Dawkins, William Albert Dembski, Daniel Dennett, Guillermo Gonzalez, John Hauptman, Ben Kelley, John Lennox, Robert J. Marks II, Alister McGrath, Stephen C. Meyer, P.Z. Myers, Paul Nelson, John Polkinghome, William Provine, Michael Ruse, Gerald Schroeder, Jeffrey Schwartz, Eugenie Scott, Michael Shermer, Mark Souder, Richard Sternberg, Deano Sutter, Daniel Walsch, Richard Weikart, Jonathan Wells, Pamela Winnick, and Larry Witham. Original music by Robbie Bronniman and Andy Hunter. Camerawork by Ben Huddleston and Maximilian Zenk. Edited by Simon Tondeur. Post-production supervisor, Patrick Tittmar. Written by Kevin Miller, Walt Ruloff, and Ben Stein. Directed by Nathan Frankowski. (Premise Media Corporation/Rampant Films, 2008, Color, 90 minutes. MPAA Rating: PG).

What’s not to admire about Ben Stein? If I were given the chance to be anyone else for just one day, it would be the monotonous economics teacher from Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, Yale Law School valedictorian, Nixon speechwriter, Comedy Central game show host, New York Times financial columnist, Ford administration attorney, Clear Eyes pitching über-Renaissance man, who’s comfortable being himself in his trademark Nike sneakers with his suit jacket and tie.

I also like that Stein’s a conservative who speaks his own mind: When Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld sent a “leaner, tougher” (read: Waging War on the Cheap) Army into Iraq in 2003, Stein was one of the few Republicans who saw through his idiocy and advocated building up the U.S. military to Cold War levels to fight the Jihadists. I also like that he’s a Hollywood fixture who nonetheless has the guts to loudly advocate for pro-life causes.

He’s also one of the sharpest knives in the drawer. While objectivists and libertarians try to paint Michael Milken as some kind of modern-day Prometheus, I still stand by Stein’s assessment, his 1992 book A License to Steal, of the junk bonds king as a swindler who defrauded investors. He’s a mensch in the best way, too: He sticks by his friends, and doesn’t let political differences get in the way of contributing to comedian pal Al Franken’s (whom I loathe, actually) Minnesota senate run.

And that’s just scratching the surface. I daresay at the rate I’m going it would take ten lifetimes to equal Stein’s prolific résumé. Despite his vast array of talents, though, I think it’s safe to say that the one thing Ben Stein is not is a first-rate biologist.

In his opening narration, Stein says,

I believe everything that exists was created by a loving God…. All along, I’ve been well aware that other people, very smart people, believe otherwise. Rather than God’s handiwork, they see the universe as a product of random particle collisions, and chemical reactions. And rather than regard humankind as carrying the spark of the divine, they believe we’re nothing more than mud and made by lightning. Somehow, that mud found a way to grow, reproduce, swim, crawl, breathe, walk, and, eventually, think.

Stein interviews a number of scientific academicians in what trying to establish the documentary’s assertion that the adherents of Intelligent Design—a position with which I am in great sympathy—are systematically being censored, kicked out of the academy, and blacklisted for daring to question Charles Darwin’s theories of the origins of species and evolution. Yet, even if the viewer were unaware of Stein’s manipulative questioning and editing—in portraying these scientists as martyrs felled by the sword of secular intolerance—it nonetheless becomes embarrassingly clear that, in number and quality, ID’s proponents are rather thin.

While I agree with much Ben Stein says regarding issues of free academic speech, much about Expelled came off as a right-wing version of a Michael Moore “documentary,” in that the movie’s designed to lead the viewer to a foregone conclusion. One segment shows Stein interviewing Guillermo Gonzalez, an astronomy professor allegedly denied tenure at Iowa State University because of his writings on ID. However, Stein left out that the professor was more likely a victim of the “publish or perish” policy that most universities foist upon their faculties.

Although I, being a Deist, believe that God created the universe, this planet, and the life that exists on it, I readily admit that those beliefs are largely matters of faith. I don’t believe religion can disprove scientific theories any more than science can explain away God. Both propositions are akin to squaring the circle. That said, if there is evidence supporting the idea of Intelligent Design (the Big Bang Theory is an excellent place to start), then I am certainly open to it.

Stein tries to make his case that there are well-respected scientists who’ve discovered evidence that an “intelligent designer” (God) created life on this planet. Fine, but we in the audience are never made privy to exactly what that evidence is,save the inability of what Stein tags “Darwinism” at explaining how everything got here in the first place. We are supposed to infer that since, A). There is no explanation, that, B). Therefore, an “intelligent designer” must have created it (which is quite reasonable, but–as Clara Peller might inquire—where’s the beef?).

Where Stein succeeds more is at poking holes into what laymen vaguely construe as “Darwinism.” He’s quite piquant in showing Darwin’s adherents as seething dogmatists, which many of them indeed are. Touchy, even, as in the case of his interview with renowned British evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins. Dawkins may be brilliant, but in this documentary he comes off as petty, peevish, and petulant. Is this really the guy you secularists so revere? Hasn’t it ever occurred to Dawkins that in his fervor to be Madelyn Murray O’Hair with Ph.D., that his many books “disproving” the existence of God (at least in the eyes of atheists) violate the first rule of logic, that one cannot disprove a negative?

Stein is clearly having fun trying to trip up Dawkins to admit even the possibility of God’s existence, and Dawkins defends his atheism, stating, with “ninety-nine per cent” certainty that there is no God. (99 per cent? Some defender of atheism).

But, again, we are brought back to the proposition of ID’s adherents, who have a lot of valid questions, but—at least using Stein’s narrative—haven’t exactly presented anything to back up their assertions. The best in this regard was Stein’s interview with mathematician and molecular biologist David Berlinski. A senior fellow at the Discovery Institute, an ID think tank, and author of the book The Devil’s Delusion: Atheism and Its Scientific Pretensions, Berlinski—a secular Jew—came off as the opposite of Dawkins. “Now,” I thought, listening to this obviously brilliant, gregarious, and inquisitive man, “finally a thinker with a real argument in favor of Intelligent Design!” Yet, after listening to him dissect Darwin’s theories from a scientist’s perspective, Berlinski really had little to say about ID. (By editing for brevity, the filmmakers do quite a disservice to Berlinski in this regard; he has quite a bit to say in making the case for an intelligent designer in The Devils Delusion, and I fear some of his arguments ended up on the proverbial cutting room floor).

One area I found quite a lot to agree with Stein was his assertion that Darwin’s ideas on natural selection—in the hands of American and British eugenicists and, later, the Germans (who were heavily influenced by American eugenicists)—can lead to the state exterminating millions of biological “undesirables,” as in the case of Nazi Germany. Oddly, this was the film’s most controversial segment, even more than its endorsement of Intelligent Design.

After the film’s release, the Anti-Defamation League, the alleged Jewish civil rights organization, took fellow Jew Ben Stein to task for “trivializing” the Holocaust: “Hitler did not need Darwin to devise his heinous plan to exterminate the Jewish people and Darwin and evolutionary theory cannot explain Hitler’s genocidal madness.”

Oh, really? I submit that this statement is ignorant of history: In Mein Kampf, Adolf Hitler spelled out his admiration for the eugenics movement and Darwin. This is no trivial matter. In the film, Stein narrates a passage from Darwin’s 1871 work, The Descent of Man:

With savages, the weak in body or mind are soon eliminated. We civilized men, on the other hand, do our utmost to check the process of elimination. We build asylums for the imbecile, the maimed and the sick, thus the weak members of civilized societies propagate their kind. No one who has attended to the breeding of domestic animals will doubt that this must be highly injurious to the race of man. Hardly anyone is so ignorant as to allow his worst animals to breed.

Stein’s detractors cried “foul!” noting that he omitted Darwin’s following sentences,

The aid which we feel impelled to give to the helpless is mainly an incidental result of the instinct of sympathy, which was originally acquired as part of the social instincts, but subsequently rendered, in the manner previously indicated, more tender and more widely diffused. Nor could we check our sympathy, if so urged by hard reason, without deterioration in the noblest part of our nature.

What has been left out of the criticisms is that Darwin was friendly, personally and professionally, with many of the larger lights in the British eugenics movement, in particular Francis Galton and Herbert Spencer. Darwin later embraced the phrase Spencer coined “survival of the fittest,” and used it synonymously with his term “natural selection” in later revisions of On the Origin of Species. Although Darwin’s later defenders have tried to distance him from Spencer’s cockamamie “Social Darwinist” writings, the fact remains this was done posthumously on his behalf; during his own lifetime, Darwin said little that could be used to contradict the leading eugenicists of his era. In fact, his son, Major Leonard Darwin, became chairman of the British Eugenics Society from 1911 to 1928, and was seen in his efforts as carrying on his father’s legacy.

Also left unmentioned by the ADL is the fact that Hitler perfected eugenics policies that in the United States, England, and continental Europe resulted in the forced sterilization and castration of hundreds of thousands, of genetic “undesirables.” Indeed, the preferred German term for eugenics was “racial hygiene,” and was carried out to the letter in the death camps such as Auschwitz-Birkenau, Dachau, and Treblinka.

I think most critics have misread Stein. He never claimed that Darwin would ever have advocated such ghastly horrors, and given his own writings, we know he would not have. What Stein’s (accurate) treatment of the linkage between eugenics and the Holocaust demonstrates is that scientists should tread with caution when making inroads into the ethical sphere, because the unintended consequences of ostensibly benign theories can have devastating effects, particularly when taken up by murderous statists (like, say, embryonic stem-cell research has the potential to unleash). Granted, Charles Darwin was no more causally responsible for the Holocaust than Immanuel Kant, Friedrich Nietzsche or Richard Wagner were, but why are these latter fair game for the assignation of blame, but not Darwin? I recommend historian Edwin Black’s War Against the Weak: Eugenics and America’s Campaign to Create a Master Race, which uncovers the dark and sickening forgotten chapters of America and Germany’s shared history.

This doesn’t change the fact that Stein was trying to take out Darwin’s theory on the origin of species, by using the eugenics argument and the Holocaust in support of debunking it.

Nonetheless, the movie has much to recommend it in recounting how the scientific community enforces its “consensus” will against dissenters, even prior to a peer-review article being published. This does not bode well for academic freedom. It is a result of government funding becoming too intertwined with scientific research. If Intelligent Design is such a preposterous set of ideas on its face, then let its adherents expose it to critical review.

The scientific “community” cannot have it both ways, dismissing ID out of hand, wallowing in the swamp of government cash while advocating the pseudoscience of “climate change.” I think Stein is onto something when he says the scientific “community” is hardly objective, and requires its members to march in lockstep.

That said, Expelled was, sadly, otherwise largely a brilliant exercise in sophistry.

Robert L. Jones is a photojournalist living and working in Minnesota. His work has appeared in Black & White Magazine, Entrepreneur, Hoy! New York, the New York Post, RCA Victor (Japan), Scene in San Antonio, Spirit Magazine (Canada), Top Producer, and the Trenton Times. Mr. Jones is a past entertainment editor of The New Individualist.

Topics: Documentaries, Movie Reviews |

John Adams (2008) – Miniseries Review

By Robert L. Jones | July 4, 2008

Paul Giamatti and Laura Linney during a moment of crisis in HBO's "John Adams"

Little Big Man

[xrr rating=5/5]

John Adams. Miniseries starring Paul Giamatti, Laura Linney, David Morse, Clancy O’Connor, Sarah Polley, Rufus Sewell, Justin Theroux, Tom Wilkinson, Danny Huston, Stephen Dillane, Samuel Barnett, Tom Beckett, John Bedford Lloyd, Jean Brassard, Ritchie Coster, John Dossett, Mamie Gummer, Steven Hinkle, Tom Hollander, Zeljko Ivanek, Ebon Moss-Bachrach, and Michael Hall D’Addario. Music by Rob Lane and Joseph Vitarelli. Cinematography by Tak Fujimoto, A.S.C., and Danny Cohen. Production design by Gemma Jackson. Costume design by Donna Zakowska. Edited by Melanie Oliver. Screenplay by Kirk Ellis and Michelle Ashford. Based on the book by David McCullough. Directed by Tom Hooper. (HBO Films/Playtone Productions, 2008, color, seven episodes/total running time: 8 hours, 21 minutes.)

Reclining on the front porch of his family farmhouse in Quincy, Massachusetts, nursing a broken foot, an aging John Adams predicts to wife Abigail his presence fading from the books to be written by historians.

“The essence of our revolution will be that Dr. Franklin smote the earth with his electrical rod, and out sprang Washington and Jefferson!”

John Adams never did fit neatly within the Holy Trinity of America’s founding fathers. It would have been too anticlimactic ever to envision him ensconced atop a pillared pantheon with our national gods of jovial wisdom, stoic heroism, and searing intellect. It would have been an act of desecration to include such a squat, crabby bulldog of a man.

In this brilliant adaptation of historian David McCullough’s weighty (but never dragging) 2001 volume, John Adams’s legacy stubbornly refuses to go away. What becomes of history’s runts with outsized cerebral gifts and aspirations? They are already cursed from the word “go.” Half their life’s work consists in overcoming skeptical patronizing by men with smaller minds, who, in a cruel twist of fate, were born blessed with larger physical stature.

Rather than using the standard biopic template—squeezing the highlights of Adams’s life into the deceptively short eight hours of this mini-series—screenwriter Kirk Ellis instead uses each episode to dramatize a crucial event that tests his protagonist’s mettle. Veteran character actor Paul Giamatti, who has made a career of playing lovable losers in movies like Sideways and American Splendor, at last portrays a man of great character and moral, if not physical, stature.

From the first episode, Adams’s integrity is put to the test. The year is 1770 and two American colonists lie dead in the cold New England snow, cut down by British muskets. The only lawyer in Boston who will take up the defense of the Redcoats accused of murder is Adams, who is not only sympathetic to the colonists’ cause against oppressive taxation but is also cousin to Samuel Adams, hotheaded ringleader of the Sons of Liberty.

He refuses to let political considerations enter his defense of Captain Preston (Richie Coster) and his men. “You may expect from me no art of address, no sophistry, no prevarication in such a cause,” he brusquely informs the accused soldiers. He also refuses to buckle under pressure when firebrand Sam (Danny Huston) questions his loyalties. “I am for the law, cousin. Is there another side?”

In the riveting courtroom drama that follows, it’s Adams’s steadfast and forthright devotion to principle that eventually carries the day, despite his dangerously unpopular cause. Even as witnesses are openly intimidated in the courtroom by rowdy Sons of Liberty members, Adams prevails upon the jury to decide the case solely on the evidence. “Facts are stubborn things,” he argues.

It is that very commitment to principle, coupled with a bullheaded stubbornness, that in 1775 propels “Plain” John Adams to the Continental Congress in Philadelphia, to become one of the first to advocate independence. While Benjamin Franklin worked behind the scenes to change minds and Thomas Jefferson silently avoided debate (though he would later pen the Declaration of Independence, at Adams’s urging), Adams alone broke through Quaker pacifist John Dickinson’s stonewalling like a battering ram, convincing the assembly to make a clean break from England.

It is after declaring independence, though, that we truly see what Adams’s principles are made of. Meeting with Jefferson in Paris, many brilliant and concise exchanges between the men reveal two opposing philosophies working towards the same goal—securing the rights of men. In contrast to Jefferson’s enlightenment notions of individual liberty resting all power in the people, Adams’s advocated a more Tory approach of checking power with power. When Jefferson (Stephen Dillane) accuses Adams of a “disconcerting lack of faith in your fellow man,” Adams is quick to rejoin: “Yes. And you display a dangerous excess of faith in your fellow man, Mr. Jefferson.” He confesses earlier—after witnessing the tarring and feathering of a British tax collector at the hands of raucous Sons of Liberty—to wife Abigail his fear of democracy backsliding into mob rule. “People are in need of government, Abigail. Restraint. Most men are weak, evil, and vicious.” It was from Adams, not Jefferson, that we got the ideal of “a government of laws, not men.”

Although portrayed as a principled man who never betrayed his country or family, John Adams is also depicted as a flawed man. But after viewing this deeply moving, indeed loving, portrait of a very imperfect man, I concluded that it was Adams’s status as a mere mortal that was the source of his wisdom. Later elected to the presidency, it is his clearheaded thinking that keeps America out of “an unnecessary war” between France and England. Although accused of “monarchist” aspirations, Adams spends much of his time thwarting Alexander Hamilton’s actual monarchical designs in trying to increase the power of the executive branch and too closely allying America with England. He also feels vindicated when America is able to secure an agreement of peace from Napoleon Bonaparte’s France. Though Jefferson is not present in the room, Adams almost seems to be addressing that idealistic enthusiast of the French Revolution when he grouses, “From monarchy to anarchy, and back to monarchy again.”

Essential to Adams’s character was his wife, Abigail, played convincingly and compassionately by Laura Linney. Adams sought her advice more than anyone else’s. More than a companion and mother to his children and hardly a yes-woman, Abigail would tell John what he needed to hear, not just what flattered his ego. Linney’s Abigail never comes off as spiteful but rather as a harsh, exacting critic who keeps Adams in check when his zeal gets the better of him. Among the most touching and genuine scenes in the series are those between husband and wife—not just personally, but also in the way they demonstrate that Adams practiced what he preached on the subject of checking powers.

In its final chapter, John Adams is also a poignant redemption story, as the shorter patriot shows himself to be the bigger man by reconciling with Jefferson, who had betrayed him during the 1800 election. The exchange of letters over the last years of the old men’s lives is related simply, through montage and voiceover, conveying the power of their ideas while simultaneously dramatizing the fact that each was incomplete without the friendship and esteem of the other. In an ending more implausible than Hollywood could have ever concocted—yet historically accurate and so singularly apropos—the two men’s lives are connected for one last time in the history of the Republic they created.

Paul Giamatti is a perfect fit for John Adams, bringing intense conviction and intellect to this role of a lifetime. His passionate brand of acting, of going for broke without ever going over the top, first made an impression on me when I saw him in Duets, playing a down-and-out karaoke singer. From that godawful script he elevated his lines to become something profound. I immediately thought Giamatti’s talent was wasted, and that he’d be a perfect Cyrano de Bergerac.

To witness Giamatti’s physical acting is to understand what made John Adams tick. Pain, anguish, and bitterness play across his face as he tries unsuccessfully to keep a stiff upper lip in the face of so many of life’s failures. The producers knew exactly what they were doing when they cast him. Giamatti is no pretty boy, not pleasing to look at—but so fascinating to watch.

I have never before been so captivated by a miniseries. The cast and production are A-list and never for a moment had that “made for television” feel that miniseries used to exude. Giamatti and Linney are joined by stellar acting from the rest of the principals, especially Tom Wilkinson as Franklin, Rufus Sewell as Hamilton, plus Dillane and Huston. The filming and production design are no less exceptional. Cinematographers Tak Fujimoto and Danny Cohen use inventive shots that are never obtrusive. One example occurs during the time Adams was quarantined in Holland with consumption: Positioning him in his box bed behind open door frames and parquet flooring, Adams seems trapped in a Vermeer painting.

We live in a perverse age, in which great men are pilloried and cut down to size. It is therefore all the more unexpectedly welcome to watch this stupendous miniseries, which shows us just how large this little man from Massachusetts loomed in America’s creation.

Robert L. Jones is a photojournalist living and working in Minnesota. His work has appeared in Black & White Magazine, Entrepreneur, Hoy! New York, the New York Post, RCA Victor (Japan), Scene in San Antonio, Spirit Magazine (Canada), Top Producer, and the Trenton Times. Mr. Jones is a past entertainment editor of The New Individualist.

Topics: Biopics, Costume Dramas, Courtroom Dramas, Dramas, Made for Cable, Miniseries |